"Hacking" Is Not A Dirty Word - A Brief Treatise on the Origins of IT Creativity

- Security Panda (you were expecting someone

- Apr 5, 2018

- 10 min read

This is something I authored back in 2010, but it is even more pertinent today. It does need updating, and I may very well do that here later, but in the meantime...

When someone brings up the term “hacker,” does the image of a chronically pale twenty- something hunched over a keyboard in the basement of their parents‟ suburban home spring to mind? Giggling and plotting neurotically or somber and taking themselves way too seriously, these introverted troglodytes want nothing more than to break into computers and make them crash 30 times a day. At least that would appear to be the case. I would argue that the truth of the matter is much different, and this bizarre image is a sad misconception that has become lodged in the mind of the average citizen. Hackers are not cybercriminals. They deserve a better portrayal by the media and recognition for the constant work they perform to improve technology for the average user. The traditional hacker might be someone who began as a dedicated coder with a desire to script something a little bit better, or a basement tinkerer who took things apart and rebuilt them to see how they could be made to work faster. The Internet was the brainchild of a hacker, and many modern computing capabilities are the work of self-proclaimed hackers. Technology users benefit from their unseen dedication every day in the form of more efficient software, increased online security, and faster Internet connections.

Originally brought into slang term use by model railroad enthusiasts in the Tech Model Railroad Club at MIT in the 1950s, the word hacker referred to someone who modified machines or equipment to suit his own ideals. Later it came into use as a positive term referring to skilled computer users who worked to test the boundaries of hardware and software. Many of the founders of the computing industry today met in a little organization called the Homebrew Computer Club, and referred to themselves as hackers (Levy, 1984). A good example of what hacking is about would be the do-it-yourself article entitled “Hacking XP” (Mathews, 2006) in the popular magazine PC World. This article does not describe ways to break into Windows XP; instead, it illustrates some typically unexplored or underutilized tools to make life with Windows XP a little bit simpler. Consider this statement from a recent Computer Sciences text, “Those who hacked took pride in their ability to write computer programs that stretched the capabilities of computer systems and find clever solutions to seemingly impossible problems,” (Nachenberg, 2002, p. 104). More attention should be paid to presenting the current ideals and work of hackers in schools to offset the primarily negative picture painted by the popular media.

The roots of the word "hacking‟ are not malicious, but unfortunately, the word has suffered in its use by the media. Much of the evil overtones that surround the term hacker are misrepresentations or simply misunderstandings. The publicity surrounding the prosecution of Kevin Mitnick is probably the most notorious example. Objections to the persistent use of the word hacker to refer to cybercriminals are widespread on the blogs and forums of the Internet, but are rarely reflected in popular media. The hacker community strongly resents the use of the word by the media to describe malicious and destructive activities. Recently, the hacker community in Slovenia drafted an open letter to the media addressing the misuse of the word hacker during reports about three suspects in the Mariposa botnet investigation (Åuklje, 2010).

This is by far not the first open letter addressing the issue. A quick search with Google for the terms “ethical hacking” or “hacker ethics” reveals a wide array of articles, blogs, and personal sentiment about the social responsibilities incumbent upon hackers.

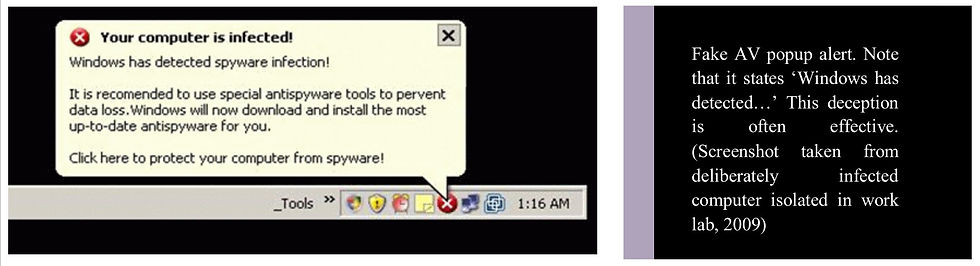

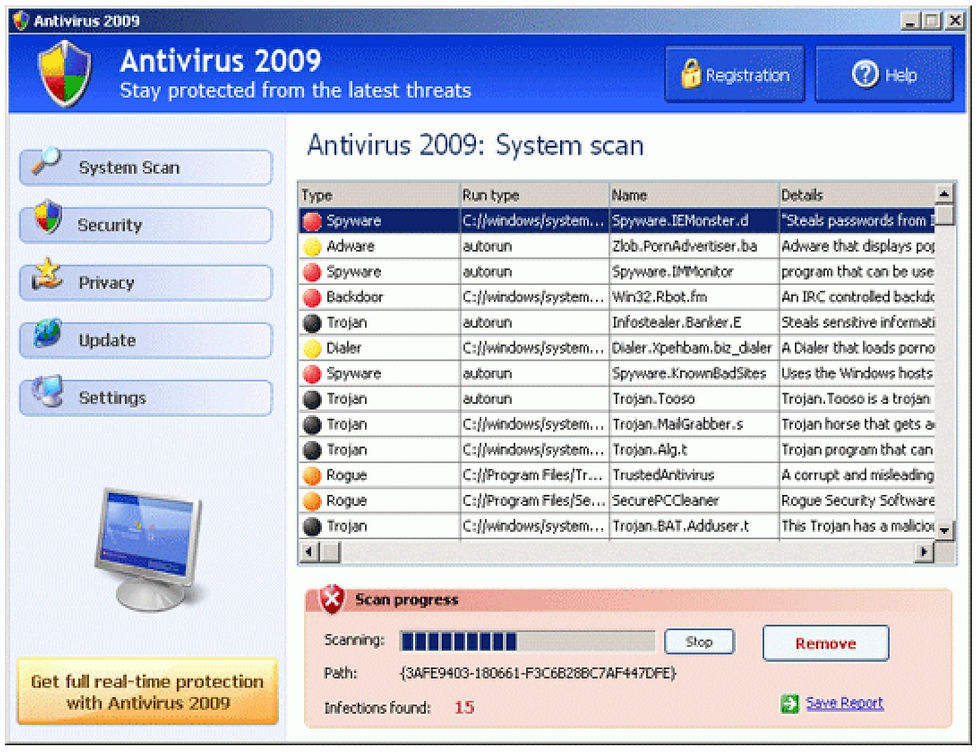

It would be ridiculous to deny the existence of the unfortunate truth in the other side of this story. Individuals, teams of people, and even organized companies are deliberately scripting malware (a blanket term including Trojans, spyware, adware, viruses and rootkits), to break into computers and steal data for monetary gain. Traditional hackers often use the term „cracker‟ to describe these miscreants because they „crack‟ systems, using software to steal or guess passwords. Once they have gained illicit access to a system, the cracker‟s goal is something far more damaging than inconveniencing a legitimate computer user. Malware is designed to collect personal information and report it to a centralized server where it is collated and can be used in identity fraud. Money and credit card numbers can be extorted by convincing the user that they need to purchase fake antivirus software, and computers can be slaved together and used for distributed denial of service attacks or spam distribution.

To discourage attempts to remove viruses by average users, malware is often designed to detect removal attempts. Improper removal can leave computers in an unbootable state or trigger deletions of folders such as My Documents or My Pictures. Personal experience removing recent malware like the Conficker worm, the Vundo-variant viruses, and the recent hybrid rootkits speaks to how nasty these infections can be.

Hackers often work to reverse engineer these products of destruction, and an excellent example of their work is the code from the Conficker worm, also commonly known as Downadup or Kido. The worm spread itself in all the standard ways, through shares and over networks. In addition, the worm could spread itself through removable drives, a new twist on an old problem. Upon infection, the worm quietly disabled the update utility, and disabled access to certain antivirus websites and applications. To all appearances, the worm did no other damage, did not attempt to subvert the infected hosts, and did not gather and report any data. A security team of hackers examined the code and determined that the worm was designed to report information about the computers it had infected and was set with a specific activation date. What the worm was designed to do upon activation was, and still is, unclear. Discovery of this information spurred tremendous activity to disable and remove this fast-spreading piece of malicious code. Once a piece of malware has been analyzed, detection and removal tools can be scripted and released over the Internet. Microsoft released a special security patch just for the Conficker worm. EEye Digital Security created a scanner capable of examining entire business networks to identify infected machines. An even simpler tool called the Eye Chart was released by Director of Malware Research at SecureWorks, Joe Stewart. This tool consisted of a series of images from security sites that Conficker was known to block. If the images couldn‟t be viewed over the Internet, the computer was probably infected. This tool is free to download and use and simple enough to allow average users to detect infection. Although the worm was ultimately harmless as the activation date came and went with no activity, there would still have been many more infected and vulnerable computers if the worm had not been so competently analyzed.

Hackers often work to discover potential weaknesses in operating system security and other applications before these vulnerabilities can be exploited. It is argued that this is only so they can trade the information online or create new malware themselves, but traditional and “white hat” hackers work with an ethical code that regulates how they treat the vulnerabilities they locate. Serious consequences exist for public disclosure of information including criminal prosecution if the information is considered proprietary. The danger of being sued by a corporation for damages in the case of a security breach always exists, even if the perpetrators had the vulnerability information before the hacker released it to the public. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) publishes an online guidebook that states it very well: “Whatever course the researcher takes, she is exposing herself in the interest of bettering security for the public,” (EFF, 2010, last paragraph). Unfortunately, there is often a conundrum to face: Is it more ethical to keep a security issue a secret from the average users in the hopes that it is not already known to malicious hackers? The alternative is to make a public release of the information, guaranteeing that malicious crackers will be aware of it but also allowing users to protect themselves and companies aware so they can begin working to make the product more secure. Charlie Miller and Colin Mulliner planned to reveal a serious Apple iPhone flaw to the public in 2009 at the well-known Black Hat convention. Miller made repeated attempts to notify Apple in advance, but Apple did not respond. An interview published in Forbes Magazine quotes Miller as stating that he had "…given them more time to patch this than I've ever given a company to patch a bug," (Greenberg, 2009, para. 7). Prior to the conference Apple did respond, and Miller and Mulliner agreed to delay the presentation so Apple would have more time to correct the issue. This response is fairly atypical, as illustrated by the chart below that highlights some of the more infamous vulnerabilities addressed at Black Hat this year. The responses in the right side of the chart are the company responses. With few exceptions the companies have worked to release security patches to consumers prior to public disclosure of the information.

Hackers are not unsung folk heroes fighting to protect an innocent public from the evil atrocities of the faceless large corporations; neither are they evil and intent on destroying the Internet. Hackers are people with a deep-seated interest in problem-solving and a love for information. For many it is a hobby, for others it is a way of life. Black Hat is not the only conference held where hackers go to disseminate information they have discovered, although it is probably one of the best known. DefCon and HOPE (Hackers On Planet Earth) are two other regular events. Companies like Apple, Microsoft, and Cisco often send their own representatives to these conventions to learn new techniques for safeguarding data and products. Hackers work with companies and the public to improve product security and stability.

This year, some of the training topics include:

Application Security for Hackers and Developers

Advanced Malware Analysis

Detecting and Mitigating Attacks Using Your Network Infrastructure.

Some of the training courses on the list bear more ominous-sounding names such as:

Assessing and Exploiting Web Applications with Samurai

Advanced Windows Exploitation Techniques

TCP/IP Weapons School 2.0

Unfortunate name choices could certainly lend an unsavory appearance to the conference and add to the argument that hackers are no more than info-pirates or cybercriminals. A moment or so spent reading the descriptions reveals that most of the classes are very clearly and unambiguously intended to teach how to identify and defend against attacks. One of the topics on the agenda this year is the discussion between the previously mentioned hacker Charlie Miller and representatives from Apple. The topic? The security issues Miller and Mulliner isolated in the iPhone. As NPR reporter Nate Plutzik (2010, paragraph 5) writes in his article preparatory to covering the 2010 Black Hat convention, “Some of the former hackers who attend this conference are more Richard Boone from Have Gun — Will Travel than Jack Palance from Shane. They know the game and are sharing their knowledge to increase cyber security.”

Like the word hacker, the lines have become ambiguous regarding the “black hat / white hat” designation. Like the old Westerns, “black hat” hackers were the bad guys working to take the systems down, and “white hat” hackers were the good guys working to protect it. The line between these terms has blurred, not to some small degree because of the Black Hat conference and popular movies such as the 1995 classic “Hackers.” The information security specialist often has a daring image to live up to and a new breed of security professional has emerged: the “gray hat.” Gray hat hackers blur the lines even further because they are often working from the outside on systems they may not be authorized to access. The motivations for doing so vary but may be linked to the potential for reward from a company for locating and revealing security flaws. Many companies engage in this form of security testing including Intuit‟s Mint.com and Facebook (Bilton, 2010). An additional motivator is the existence of a thriving underground market for new security loopholes, which can be sold or traded online. New malware is then designed to exploit the vulnerability before it can be patched. Depending on the flaw and the product, the price tag can be considerable. Gray hat hackers cause the most disruption and confusion. They do not always make much of an effort to notify or work with a company before releasing information about a security flaw to the public. As previously mentioned, this behavior can court serious legal and financial consequences.

Although it is undeniable that criminals use computers and the unique properties of the Internet to commit crimes, it is wrong to assume that hackers are criminals. Hackers play a vital role in keeping the Internet safe, and often prevent companies from allowing insecure products to leak personal data or allow crackers to infiltrate systems. The media should present a more balanced picture of what is occurring and how much work hackers do to fight malware. They should also respect the hacker community's desire to retain the term hacker as a positive phrase and use some alternative word such as “cybercriminal” or just the old fashioned “suspect” as they would for any other crime. Educational facilities should follow suit, providing background information about the current computer age that reflects the imagination and spirit of hackers then and now. Hacking is not and should not be a dirty word.

References

A "Grey Hat" Guide | Electronic Frontier Foundation [EFF]. (n.d.). Electronic Frontier Foundation | Defending Freedom in the Digital World. Retrieved July 31, 2010, from http://www.eff.org/issues/coders/grey-hat-guide

Å uklje, M. (2010, September 3). Open letter to the media about the misuse of the term "hacker". Linux Today - Linux News On Internet Time.. Retrieved September 19, 2010, from http://www.linuxtoday.com/infrastructure/2010080302935OPCYDV

Bilton, N. (2010, July 25). Hackers With Enigmatic Motives Vex Companies. New York Times, p. B5. Retrieved July 31, 2010, from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/26/technology/26security.html?src=me&ref=technolo gy Greenberg, A. (2009, July 28). How to Hijack 'Every iPhone In The World'. Forbes.com. Retrieved July 31, 2010, from http://www.forbes.com/2009/07/28/hackers-iphone-apple- technology-security-hackers.html Levy, S. (1984). Hackers – Heroes of the Computer Revolution (pp. 202-203). NewYork, NY: Doubleday & Co., Inc. Mathews, D. (2006). HACKING XP. PC Magazine, 25(19/20), 130. Retrieved July 29, 2010

from the University of Phoenix MasterFILE Premier database. *

Nachenberg, C. (2002). Hacking. Computer Sciences Volume 3 (pp. 104-107). New York: Macmillan Library Reference. Retrieved July 29, 2010 from the University of Phoenix Gale Virtual Reference Library * Plutzik, N. (2010, January 29). Black Hat 2010: Hackers Gather to Prevent Hacking? : NPR.

NPR : National Public Radio : News & Analysis, World, US, Music & Arts : NPR. Retrieved July 31, 2010, from http://www.npr.org/blogs/alltechconsidered/2010/01/blackhat_2010_hackers_gather_t.ht ml

Stewart, J. (2009) "Conficker Eye Chart." – ACATTAG. Retrieved Sept. 19, 2010, from <http://www.joestewart.org/cfeyechart.html>.

*From University Library

Comments